Ethics: In a Fast-Changing World

Experiential Education

This module focuses on

- What ethics are

- Why ethics are important

- Ethics in a fast-changing world: ‘cognitive based ethics’

What are ethics?

Matters of Definition

The Merriam-Webster Dictionary (online) defines ethics as:

A set of moral principles...a consciousness of moral importance.

Ethics are rules (self- or socially-imposed) that help us decide what is morally good or morally bad (that is, moral wrongs). For most of us, ethics is ‘doing the right thing’, whether others know about it, or not.

Of course, the ‘right thing’ can be different for everyone. It can depend on our own values, or those of our society or culture; it also can be influenced by where we are and who we are with:

Doing the ‘right thing’, choosing the ethical option or behaving according to your own or your organisation’s set of values can someone be a difficult choice. What guides you in situations like this?

Acting with integrity means acting according to your own personal set of values and principles, which are different for everyone. Behaving ethically means behaving according to a set of standards that are the same for everyone, at least for everyone in the same culture. Acting with integrity and behaving ethically build your credibility.

What are moral wrongs?

Cole (2013, p. 177) tells us that ‘most cultures share many ethical standards’. Can you think of anything that is considered morally wrong in Australia? Then there are sub-cultures within the Australian culture. You can probably think of a few actions that we as a nation consider not right, but here are a few to get you started:

The academic culture

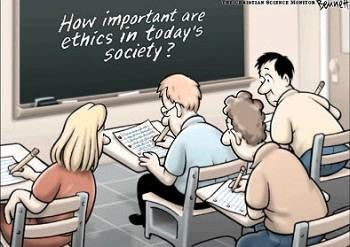

Committing plagiarism: using someone else's work without acknowledging the source.

Cheating in exams.

The business culture

Charging unfair prices for services or products.

Giving bad customer service.

The workplace/employee culture

Constantly turning up late for work.

Not giving fair work for pay.

The sports culture

Taking performance-enhancing drugs.

Making racist comments.

The social culture

Being disrespectful of others.

Trashing the environment.

There are many more such sub-cultures in Australia, of course, and many more actions that most people in the country consider to be morally wrong. Many, or most, of course, go across cultures.

Why are ethics important?

(Canepa n.d.)

(Canepa n.d.)

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43BC), statesman, orator, and writer, said:

What is morally wrong can never be advantageous, even when it enables you to make some gain that you believe to be to your advantage. The mere act of believing that something wrongful course of action constitutes an advantage is pernicious.

Ethics are important for our own sense of worth, and for the good of society. Jeff Landauer and Joseph Rowlands (2001, n.p.) go so far as to say that ‘ethics is a requirement for human life’. ‘Without it’, they suggest (2001, n.p.), ‘our actions would be random and aimless. There would be no way to work towards a goal because there would be no way to pick between a limitless number of goals’. Flawed ethics can be a stumbling block on our way to success. In other words, ethics help us along life’s journey.

How do we know when we are doing the right thing?

Sometimes doing the ‘right thing’ can be ‘awkward, inconvenient or uncomfortable’ (Cole 2013, p. 176). Can you think of any examples where we can do things that we know are not exactly right, but we do it anyway?

I can admit that there have been times when I have not put money into the parking meter (because I’m just running into the shop; or it is the end of the day and the parking inspectors will not be checking …) and in effect, I know this is stealing from the local Council. Not a big moral wrong, perhaps, but this really is only a matter of degree (see below about ‘crossing the line’). Another scenario to which I am sure many can relate: I find $5 in the street – great!, I think, and pocket the money. I find $500 in the street – I take it to the police station (and hope that no-one claims it so I can pocket it). Where is the cut-off point for whether I keep the money, or hand it in?

Here are some questions we can ask ourselves to help us make decisions about whether to proceed, or not, with an action we are not sure is morally right. They were suggested by Norman Augustine, former CEO of Lockheed Martin:

Is it legal? If someone did it to me, would I think it was fair? Would I be comfortable for it to appear on the front page of the newspaper? Would I like my mother to see me do it?

If you can answer ‘yes’ to all four questions, then what you are about to do is probably ethical.

Crossing the line: when do ‘small’ moral wrongs become ‘big’ ones?

There is not an easy answer. I’m not sure if there is an answer. For example, where is the line that says, ‘This parking meter theft from the Council is okay but embezzlement from the Council is not?'

Here is a YouTube video by someone who crossed that line, Diann Cattani, Convicted Fraudster (2012):

The Slippery Slope to Major Fraud-Diann Cattani-Fraud Magazine-January/February 2012 | 4:03

Diann suggests several times that she ‘crossed the line’, although the original mistake was not of her making. She had the opportunity to cross back again but rationalised against it, and thus set herself on the path to a conviction for fraud.

Linda Klebe Treviño and Michael E. Brown (2004, p. 70) tell us that it is a myth that ethics are easy: there is no ‘big red flag’ that warns us when there is an ethical issue ahead. Taking the moral option is a complex matter, they suggest, with four stages:

Becoming aware that there is a moral issue.

Making a judgment – that is, deciding which specific action is morally justifiable.

Becoming motivated – committing or intending to take the moral action.

Showing moral character – actually following through.

Ethics in a fast-changing world: 'Cognitive empathy-based ethics'

Once upon a time when we talked about ‘tomorrow’, we meant ‘some time in the future, perhaps a decade away’. Now, when we say ‘tomorrow’, we can literally mean ‘the day that arrives straight after today’. Part of our foray into the concept of ethics must include how to be ethical in a fast-changing world.

Change, suggests Henry De Sio (2015), is not coming – it’s here. With the Internet and other technology, today’s world is very different from yesterday’s. And tomorrow’s will be different again. We must be willing to change and to think differently, or we will be left behind. This, considers De Sio, is particularly relevant when we are in a leadership role.

Rules cannot keep up with the fluidity and rapidity of change, therefore ‘cognitive empathy-based ethics’ (De Sio 2015, p. 5) are essential:

Empathy is the ability to share, understand, and acknowledge the feelings of others without having those feelings explicitly communicated. Empathy can be engendered, for example, by experiencing a situation that someone else has experienced, such as grief from a loss, joy from a moment of delight, or pride from achievement. Empathy is nonjudgmental.

Cognitive empathy is when we consciously drive to recognise and understand another’s emotional state.

Cognitive empathy-based ethics, then, are when we make a conscious effort to do the right thing, not necessarily based on rules or even social mores (because these may not have caught up yet), but on considering the other person.

Activity

To consolidate your learning on this module, go to the engagement activity in PebblePad and answer the 5 questions which will be saved into your Asset store. You will then be able to move it into your Professional or Academic Portfolio (if appropriate).

References

Canepa, G n.d., Polus media affiliate marketing, image, Pinterest, viewed 15 September 2021, <https://www.pinterest.com.au/pin/368591550722442641/>.

Cole, K 2013, Management theory and practice, 5th edn, Pearson, Frenchs Forest.

De Sio, H 2015, ‘New literacy and the changemaker generation: why empathy is as important as reading and math’, The Transformative Nature of Education: Underpinning Social and Economic Transformations International Symposium, Hobart, viewed 22 April, 2016, <https://www.ashoka.org/sites/www.ashoka.org/files/New-Literacy-for-Changemaker-Generation.pdf>.

Landauer J & Rowlands J 2001, Importance of philosophy, viewed 27 April 2017, <http://www.importanceofphilosophy.com/Ethics_Main.html>.

TheACFE 2017, The slippery slope to major fraud-Diann Cattani-Fraud Magazine-January/February 2012, YouTube video, viewed 15 September 2021, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cvQEwT5_uFw>.

Treviño LK & Brown ME 2004, ‘Managing to be ethical: debunking five business ethics myths’, Academy of Management Executive, vol. 18. no. 2, pp. 69-81.