Leading Change

Experiential Education

What you will learn:

- The concept of 'me' to 'we'.

- Three key steps in understanding ourselves: finding our talent, knowing our values, and meaning-making.

- Creating meaningful change is the most important step in the process of 'me' to 'we'.

- How to be a leader during a process of change.

The 'Me' and the 'We'

According to Mike Morrison (2007, p. xvii), Dean of Studies at Toyota University, the central practice of leading is ‘creating meaningful change’, which is the final step on the path from ‘me’ to ‘we’.

What is the concept of the ‘me’ and the ‘we’? It is simply the idea that we can more effectively and fully understand and lead others when we fully understand ourselves. Morrison (2007) suggests three key steps in the process of gaining insight into ourselves:

- Knowing and understanding and starting from the one unique talent that defines us.

- Promise making – understanding the values we hold and keep.

- Meaning making – the ability to reflect on and reframe our experiences.

Let’s think about these three steps.

One Unique Talent

Each one of us is particularly good at something. Usually we find that the ‘something’ that we’re good at is the same ‘something’ that we have a special interest in, or are passionate about, and enjoy. For example, I am particularly good at proofreading.

I remember as a very young adult feeling embarrassed that I always noticed the spelling errors in letters I received from friends and family. I did not tell anyone about this at the time – I just assumed I was not a very nice person. At the same time I was very good at English at school, and developed a love of the language and its many moods and uses. It was not until many years later (after I came to university as a mature aged-student, in fact) that I realised that I actually had a special skill that matched a passion, and I am now able to use it to help others to bring their written work up to the standard that they wish, for example for a thesis or a book chapter. My guilty secret was actually the beginning of using a talent.

As leaders, we need to recognise our own special talent – and also acknowledge the special talents of others.

Think about your special talent - something you enjoy doing, and are very good at. The take it a step further: are you using that talent to enrich your own life? For example, are you in a job where you can use your special talent?* More importantly as a leader, are you using your talent to help other people?

*This is also known as being on the right seat on the bus.

Promise - Making - Our Values

Personal values are the promises we make to ourselves and others.

Personal Values

There are many ideas of what ‘values’ actually are. A quick Internet search brings up a multitude of sites. Here are some that turn up in most lists when people are asked to name their highest-held values: integrity, honesty, friendship. It is said that a clash of values is behind most conflict.

Think about the values you hold dear. Write down five, then put them in order of priority.

Universal Values

Universal values are values that are common to all humanity. Again, there are a multitude of sites you could find on the Internet relating to universal values, and you will find that not every idea of what the basic universal values are is the same. However, there is a lot of crossover.

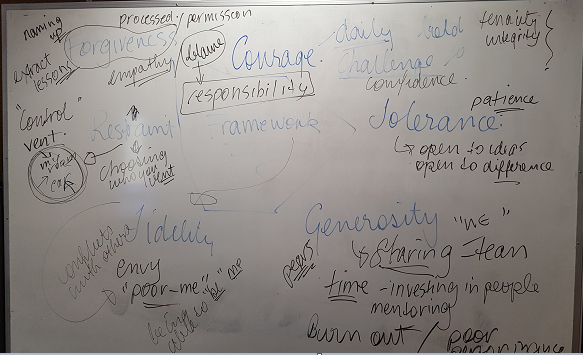

One example is from a book by Stephanie Dowrick, Forgiveness and Other Acts of Love (2010). This book is available online, and there are also links to Stephanie talking about the six values that she espouses, and why she espouses them. These are: courage, fidelity, restraint, generosity, tolerance and forgiveness.

Here is a photo of a recent whiteboard examination by students of Stephanie’s list:

Perhaps you could create a framework of your own values and think about them, especially in a context of leadership.

Meaning-making – reflect and reframe

Identify an event or moment in your life in which something did not go as you had hoped. How did you feel? What did you do? Did you pause and make some meaning from the event? Morrison (2007, p. 51) suggests that we need a ‘sense of purpose’. Sometimes, especially at the time of life’s big challenges, we can lose this sense of purpose. Morrison (2007, p. 52) provides us with three questions that we can ask ourselves when things do not go quite right:

- What does this mean to me?

- What is the meaningful thing to do?

- What new meaning can I create from the experience?

Morrison (2007, p. 60) also suggests that there are two critical capabilities that help make the meaning-making process come to life:

- Reflection (the art of thoughtful thinking).

- Reframing (the capacity to take a difficult experience and see beyond it).

This hearkens back to the reflective cycle – we need to reflect on events, make some meaning from them, make decisions about how we would handle similar situations in the future, and move on.

It also links to acknowledging that we cannot change the past. That does not of course mean that we have to forget what happened – it just means that we have not been caught in ‘analysis paralysis’ – we have moved further on in the reflective cycle.

You will recall I mentioned above how embarrassed I used to feel about automatically noting my family and friends’ spelling errors in very personal (usually hand-written) mail. Once I realised that I have a special talent in the English language, I was able to accept that although I couldn’t go back and change my feelings of embarrassment, I could move on, and use my new understanding of myself to help others. Not only has my reflection brought me to realise my own talent, however: it has also enabled me to accept that everyone has special or unique talents, and they are not necessarily the same as mine.

Treading the 'We' path and creating meaningful change

Once we have a clearer understanding of ourselves, says Morrison (2007), we can more effectively tread the We path. Again, he suggests three steps:

- Serving others: ‘developing a personal orientation that moves us from self-interest to service’ (p. 78).

- Caring: ‘they don’t care what you know until they know that you care’ (p. 96).

- Creating meaningful change ‘captures the essence of what it means to lead’ (p. 108).

Morrison (pp. 103-08) then looks more deeply at this third step:

- Creating: Leaders ‘don’t command—they facilitate, bring to life, make new, inspire and build’ (p. 103).

- Meaningful: The change must be ‘as service to something beyond ourselves’ (p. 103).

- Change: Change is happening and going to happen. What leaders need to do is make it meaningful.

Creating meaningful change as leaders

Adapting to change is not always easy. In the workplace, those who have the responsibility to create and to lead the change process face two challenges: recognising and adapting their own practices, and bringing along the people involved. According to Ron Heifetz and Don Laurie (2001, p. 58) ‘for most senior executives, providing leadership and not just authoritative expertise is extremely difficult’.

Leaders are prepared to let others play their part. The focus of the challenge must shift to the other people involved and away from the leader’s own positions of authority based on their competence in problem-solving:

Solutions to adaptive challenges reside not in the executive suite but in the collective intelligence of employees at all levels, who need to use one another as resources, often across boundaries, and learn their way to those solutions.

Leaders are aware that change can cause distress. Norms are challenged (how often have you heard the words, ‘But we’ve always done it like that!’?), personal values might be tested, and employees may feel out of their depth.

Overcoming these challenges

Heifetz and Laurie (2001) have suggested six principles for helping overcome the above two challenges:

- Get on the balcony.

- Identify the adaptive challenge.

- Regulate distress.

- Maintain disciplined attention.

- Give the work back to the employees.

- Protect leadership voices from below.

Let’s look at these one by one.

1. Get on the Balcony

Briefly, this is the concept that in order to keep an objective overview we need to take a step back, to take ourselves metaphorically to a place where we can see what is actually happening, the people involved (including ourselves), and the patterns that are forming. The information gained can help us as leaders to see the context for change, where change may need to be created, and the adaptions that might be required. For more on this idea, see the module entitled ‘Adaptive Leadership’.

2. Identify the Adaptive Challenge

Meaningful change, rather than ‘change for change’s sake’, requires diagnosis of what the problem is. More deeply, however, it also requires an understanding of any underlying or hidden problems: sometimes these are not what they appear to be on the surface.

Diagnosis may mean looking in several places. Three of the important areas to be taken into account by leaders are:

- The views of the people involved: inside and outside the organisation.

- The conflicts underlying surface-level disputes: often these are values-based.

- Themselves. Leaders embody the adaptive challenges facing any organisation: ‘no executive can hide from the fact that his or her team reflects the best and the worst of the company’s values and norms’.

(Heifetz and Laurie 2001, pp. 62-3)

3. Regulate Distress

According to Heifetz & Laurie (2001, pp. 64-5):

Adaptive work generates distress. Before putting people to work on challenges for which there are no ready solutions, a leader must realize that people can learn only so much so fast. At the same time, they must feel the need to change as reality brings new challenges. … A leader protects people by managing the rate of change.

To help alleviate any employee distress at change (at any stage – proposal, implementation, or practice), it is important that leaders:

1. Give employees time and space to discuss the issues, in a safe environment.

2. Provide direction:

- Define the key issues and values.

- Control the rate of change – don’t try to do it all at once.

3. Manage the tension: resisting any pressure to restore the status quo, raising the tough questions, and communicating presence and poise.

4. Maintain Disciplined Attention

Heifetz and Laurie (2001, p. 67) suggest that ‘disciplined attention is the currency of leadership’. But what does that mean?

It means that leaders address competing perspectives rather than resorting to the ‘quick fix’. It means leaders understanding that everyone with whom they work have different experiences, different values, different work habits. It means bringing conflict out in the open, and using the situation as a source of learning and creativity while avoiding scapegoating.

It is allowing the issues to be reframed by all involved: ‘people can learn their way to collective solutions when they understand one another’s assumptions’ (Heifetz & Laurie 2001, p. 67). It means helping employees to realise and accept that they may need to compromise and adapt in order to advance a solution rather than creating another problem.

5. Give the Work Back to People

Getting people to assume greater responsibility is not easy. Not only are many … employees comfortable being told what to do, but many managers are accustomed to treating subordinates like machinery that requires control. Letting people take the initiative in defining and solving problems means that management needs to learn to support rather than control. Workers, for their part, need to learn to take responsibility.

This means acknowledging that everyone sees the institution (for whom they work) differently. Each person has particular information and skills, and sees different needs and opportunities. Allowing people to utilise their knowledge and skills can only enrich an organisation, and help it through the change process.

The deeper sense of trust and confidence that this can bring can also encourage people to assume greater responsibility, rather than them simply looking up the chain of command and expecting someone ‘up there’ to identify the challenges and find the solutions.

At the same time, it means that leaders support their people. Support can mean many things: providing resources; having people’s back when things go wrong; creating a culture of empathy and trust; and providing a caring environment:

It has been my personal experience that organizations where leaders sincerely care about the well-being of their people than they do productivity or profitability generally see a greater sense of enthusiasm and engagement within the ranks. The culture is far more supportive of employees' ideas, contributions and team efforts. In return, employees will naturally take ownership of the outcomes, and profitability organically results. When supervisors, managers and leaders sincerely care, their direct reports generally feel more appreciated and reciprocate it.

6. Protect Voices of Leadership from Below

The sixth principle suggested by Heifetz and Laurie (2001) is the concept that potential leaders in organisations can sometimes be overlooked or silenced as ‘whistle-blowers’, or ‘creative deviants’. The voices from ‘below’ are often not articulate, lack confidence, and are over-loud or over-passionate, often at inconvenient times and places. A good leader, according to Heifetz & Laurie (2001, p. 69), will recognise that:

...buried inside a poorly packaged interjection may lie an important intuition that needs to be teased out and considered. To toss it out for its bad timing, lack of clarity, or seeming unreasonableness is to lose potentially valuable information and discourage a potential leader...

When change is happening, then these voices must be listened to. They might be bringing a perspective that provokes rethinking, that avoids the ‘quick fix’, and that helps the process of leading change to run that little bit more smoothly.

Heifetz and Laurie (2001, pp. 71-2) conclude their six principles as follows:

As a rule of thumb, when authority figures feel the reflexive urge to glare at or otherwise silence someone, they should resist. The urge to restore social equilibrium is quite powerful, and it comes on fast. One has to get accustomed to getting on the balcony, delaying the impulse, and asking, What is this guy really talking about? Is there something we’re missing?

Summary

Which bring us back to getting on the balcony, the first of Heifetz and Laurie’s (2001) six principles to help leaders lead through the difficult processes of change. A leader would find it difficult to work through the other five principles if they did not have a clear picture, at all times, of what is going on.

To recap, creating meaningful change starts with understanding ourselves (the me), enabling us to understand others (the we) – in the workplace, in the community, in our personal lives. There are three steps to understanding the me: knowing our special talents, knowing our values, and reflecting and reframing to make meaning. Once we have a deep insight into ourselves, we can begin to acknowledge that those with whom we deal also have special talents, their own values, and their own meaning-making (based on their own experiences) – and that these are not always the same as ours. Leaders hear the voices of others, no matter at what level they may appear in an organisation.

Once we as leaders understand the me of others, we can start bringing them into the we of the team.

To review a module on team roles please click below. We are also providing the link to the ‘Group Development’ module, which we encourage you to complete before doing ‘Team Roles’

You may recall Marty Linsky from the module on Adaptive Leadership. If you would like to hear him speak about leading change watch the clip below:

Adaptive Leadership-Leading Change | 21:00

References

Dowrick, S 2010, Forgiveness and other acts of love, Allen & Unwin.

Heifetz, RA & Laurie, DL 2001, ‘The work of leadership’, Stephenson Mansell Group, viewed 20 July 2017, <http://smgrp.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/The-Work-of-Leadership-Heifetz.pdf>.

Linsky, M 2011, Adaptive leadership – leading change, TedTalk 13 April, viewed 20 July 2017, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=af-cSvnEExM>.

Morrison, M 2007, The other side of the card: where your authentic leadership story begins, McGraw Hill, New York.

Pickard, S 2014, ‘How a caring leader can create a culture of support’, Brandman University, Irvine, California, viewed 24 August 2017, <https://www.brandman.edu/blog/how-caring-leaders-can-create-culture-of-support>.

Developed for the Experiential Education Program for the Associate Degrees, University College, Dr Christine Angel, 11 September 2017