Reflective Thinking and Writing

Experiential Education

Overview

What you will learn:

- What is reflection and why it’s important

- Several models of reflective cycles

- How to write a reflection

Introduction

Reflection is an important part of the learning process. It involves thinking critically about one's experiences, actions, and outcomes in order to gain deeper insights and understanding.

Sometimes the reflective thinking and writing process can be difficult, and models have been developed over many years as a method of helping with the process. This module will cover the importance of reflective thinking and then provide guidance on how you might approach a piece of reflective writing.

So, what is reflection?

Reflection is a deliberate process of examining our experiences to gain deeper insights. It involves thinking critically about what happened, why it happened, and how it affects us.

To put this simply:

reflection is serious and careful thought, that helps the thinker create meaning from an experience, and informs their decisions in the future for the benefit of themselves, and of others.

By engaging in reflection, we can better understand our actions, emotions, and thoughts, leading to personal growth and improved decision-making. This process is not just about looking back but also about planning future actions and responses based on what we have learned.

Here is one scholarly definition:

...reflection is not an end in itself but a tool or vehicle used in the transformation of raw experience into meaning-filled theory that is grounded in experience, informed by existing theory, and serves the larger purpose of the moral growth of the individual and society. It is an iterative, forward-moving spiral from practice to theory and theory to practice.”

(Rodgers' quote explains that reflection transforms experiences into meaningful lessons by combining personal insights with established theories. This process promotes moral growth in individuals and society and involves a continuous back-and-forth between practice and theory).

Sounds good but, how do we reflect?

There are many ways to undertake the process of reflection. We often do it without realising what we are doing. Think back to something that has happened, that made you stop and think about it. You might have asked yourself, Why did that happen? Or I knew that was going to happen, but why did it turn out as it did? Or Gosh, that didn’t go as planned! What could I have done better? Next time I will...

Sometimes these thoughts just flit through our heads; sometimes they require deeper consideration, and actively putting in place processes to ensure more optimal outcomes. We can simply think the situation through, or talk it through (with ourselves, through a recording, with another party), and we can write it through.

It is not always easy to make sense of situations however, and then to write them in a logical progression, with deep reflection. One useful method is to follow a reflective cycle, also known as a model of reflection, or experiential learning cycle.

Why is reflection important?

Some of the reasons reflection is important are identified below:

- Enhances understanding

Reflection deepens our comprehension of experiences by encouraging critical thinking and connecting new insights with existing knowledge. - Encourages critical thinking

Reflection challenges us to analyse our beliefs and assumptions, fostering a deeper understanding and more nuanced perspectives. - Facilitates personal growth

By continually assessing our experiences, reflection helps us identify strengths and areas for improvement, leading to ongoing self-development. - Reinforces learning

Reflective practice solidifies knowledge by connecting new experiences with prior learning, making it easier to recall and apply information. - Encourages goal setting

Reflection helps us evaluate our progress and set realistic, achievable goals based on past experiences and future aspirations. - Fosters problem-solving skills

Reflecting on challenges and their resolutions enhances our ability to think creatively and develop effective solutions. - Improves decision-making

By considering past outcomes, reflection informs better choices and more strategic planning in future situations. - Enhances emotional intelligence

Reflection helps us understand and manage our emotions, improving our ability to empathise and communicate with others. - Encourages lifelong learning

Reflective practice promotes a mindset of continuous improvement and adaptability, essential for personal and professional growth.

Models of Reflection

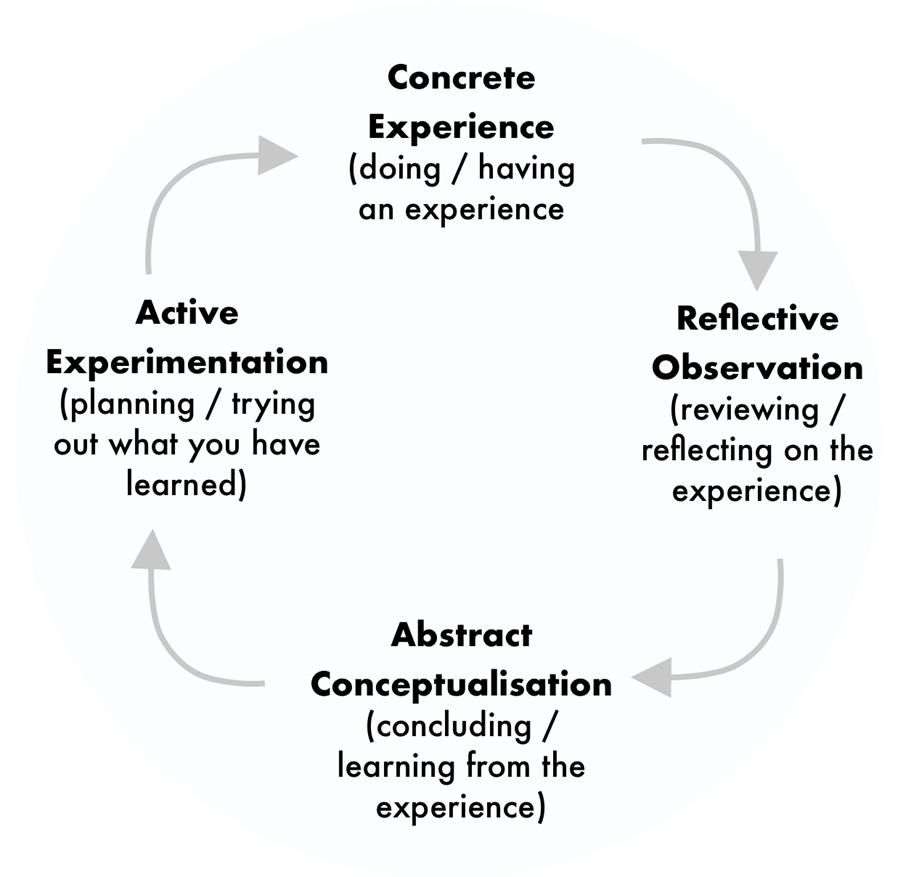

A model, or reflective cycles, are a way of graphically illustrating or representing an idea, and have been used to engage in reflective practice. When using any reflective cycle, it's essential to adapt it to the specific context and assessment task. These models provide a structured framework, but the depth and quality of reflection depend on the learner's willingness to engage in critical thinking and self-exploration. Possibly the most well-known reflective models, upon which a lot of current ones are based, is David A. Kolb’s reflective learning cycle. His model (below) was postulated in 1984 (p. 42).

Kolb’s work is recognised as presenting the foundations for learning from experience.

In 1988 Graham Gibbs created a structured approach to reflection, which is still commonly used today. Gibbs’ Reflective cycle guides you through each step of the reflection process.

Although you can start anywhere, this guidance starts at the top and works its way around clockwise. A template has been provided for you below.

And of course, no plan is complete until you put it into effect – actually applying all you have learnt from the whole experience. Which brings us back to ‘event’ …

And to one last suggestion: should a similar event occur, revisit this cycle. Every event is different, and each time we can gain a deeper insight into ourselves and others. Learning is lifelong, and learning about ourselves is no different.

How to start writing each section: a practical suggestion

As with the table building example at the beginning of this module, writing a reflection is a skill that can be learnt, and one way of learning how to do it is to do it.

However, sometimes it is hard to know where/how to start: writing does not always come easily, and even writing 250 words (as suggested for the first section) can sound rather daunting.

A suggestion to get started

'First, name up the experience. For example: ‘I went on a field trip as part of my University College course’.

Second, write one sentence about the experience against each of the six sections. Here are examples:

1: Description

‘The field trip was to the Ben Lomond mountain ranges where I took part in analysing the low land Tasmanian native plants’.

2: Feelings

‘I felt elated and excited, but as the day went on I started to feel a little trepidation about my ability to do the tasks that people were demonstrating; by the end of the day I felt a little overwhelmed but I did learn a few things.'

3: Evaluation

‘The interaction with company employees and seeing a little of what they do was useful; however, some of the tasks looked difficult to learn’.

4: Analysis

‘Looking at my experience objectively and honestly, my thought that the tasks looked difficult to learn might have been contributed to by the fact that I became inattentive as the day progressed, and some of the employees did not explain things as clearly as I would have liked’.

5: Conclusion

‘On reflection, I realise that I might need to be a little more attentive next time, and perhaps ask different questions to ensure that I receive the information I really need’.

6: Action Plan

‘Next time I go on a field trip (or a similar experience) I plan to be a little more prepared, perhaps by having some questions ready, and also I plan to listen to the answers’.

Third, go back to each sentence, and start expanding on it. Use the questions in each section above as a guide. You will find that now you have the outline down (that is, your plan) you will find it easier to add the details.

Reflective writing is an essential skill for personal and professional development. It allows you to analyse your experiences, understand your emotions, and learn from your actions. In this exercise, Here's an example of reflective writing that illustrates how to apply a reflective model in practice, specifically using Gibbs' Reflective Cycle:

Description:

During my last team project, I was responsible for coordinating tasks among members. We faced challenges in communication, which affected our project timeline.

Feelings:

I felt frustrated and stressed due to the miscommunications. I also felt a sense of responsibility for not anticipating these issues.

Evaluation:

Some team members missed deadlines, which caused delays. However, the experience highlighted the importance of clear communication and regular check-ins.

Analysis:

The main problem was the lack of clear communication channels. We relied too heavily on emails, which sometimes got overlooked.

Conclusion:

I learned that effective communication is crucial for teamwork. Regular meetings and a dedicated project management tool could prevent such issues in the future.

Action Plan:

In future projects, I will set up weekly check-ins and use a project management tool to track progress and deadlines. This will help ensure better communication and accountability among team members.

Two other models of reflection worth considering

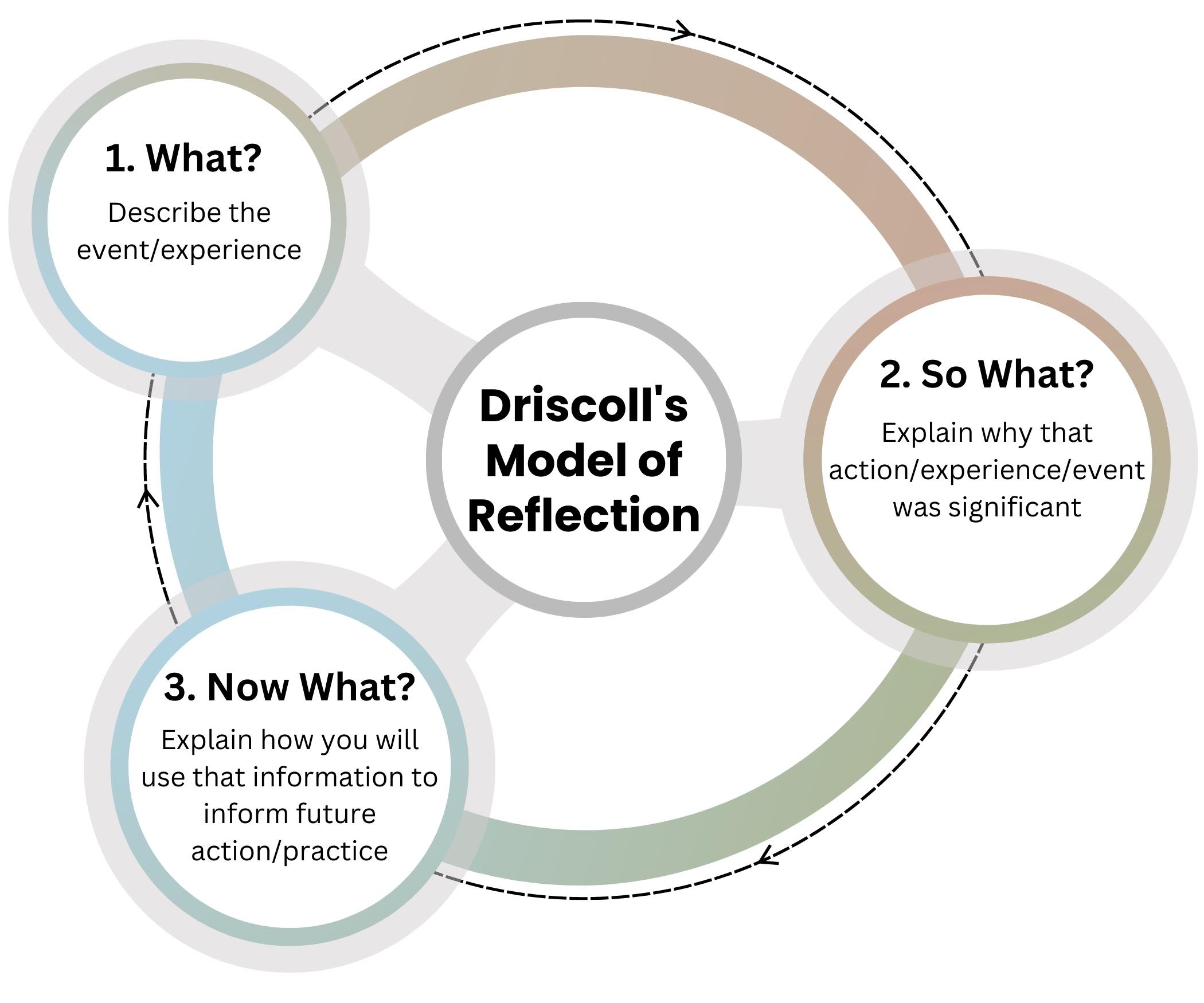

Driscoll’s Model of Reflection

(Driscoll 1994)

(Driscoll 1994)

Driscoll’s Model of Reflection is structured around three key questions: "What?", "So what?", and "Now what?". This model encourages individuals to describe an experience (What?), analyse the significance of the experience (So what?), and consider future actions (Now what?). By systematically addressing these questions, the model helps individuals gain deeper insights, learn from their experiences, and plan for future improvements.

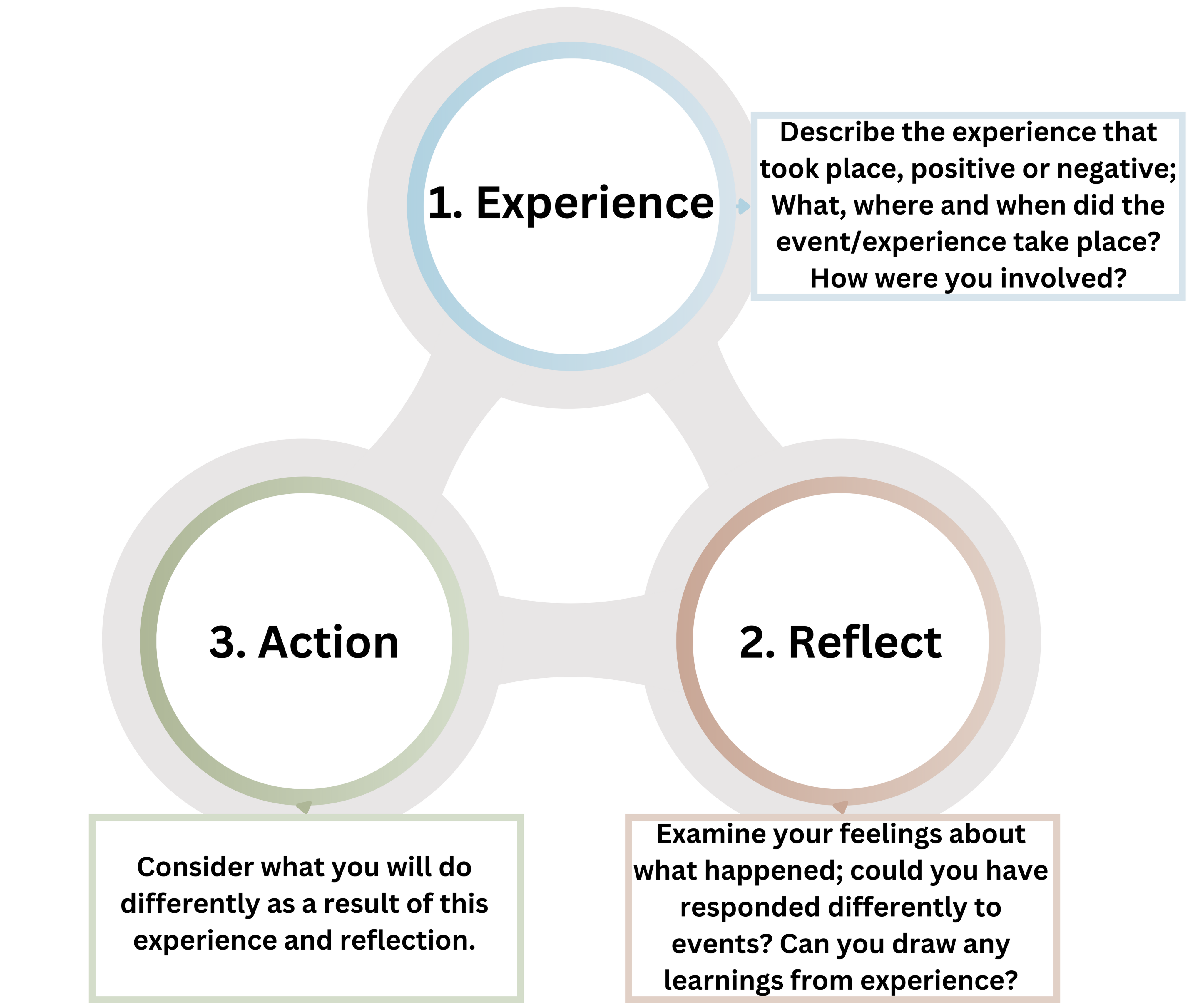

The ERA cycle

The ERA cycle, created by Melanie Jasper (2013) has only three parts as well:

The ERA Cycle stands for Experience, Reflection, and Action. This model guides individuals through a continuous loop of learning and improvement. First, individuals Experience a situation, then they Reflect on what happened and why, gaining insights and understanding. Finally, they take Action based on their reflections, applying new knowledge to future experiences. This cycle promotes continuous personal and professional development by encouraging ongoing reflection and adaptation.

Elements of Reflective Writing

We’ve established what reflection is and why it’s important. We’ve also shared some of the models, or frameworks, that can guide you in the reflective writing process.

| When it comes to writing reflectively, here are five key tips to help you write effectively: |

|---|

|

Importantly, while reflective writing is a more personal form of writing, it is not informal in style and tone. First person, ‘I’, is used to convey your experiences, but your language needs to remain formal and concise.

Finally, reflective thinking and writing involves integrating your discipline content into the experience, therefore it is common and necessary to include theory into your writing. In doing so, be sure to use in-text citations.

Further Resources

Here are some recommended YouTube videos that discuss reflective practice and can cater to different learning preferences:

Examples of Reflective Practice - This video provides real-life examples of how reflective practice can be applied, making it practical and relatable for learners. Watch it here (YouTube).

Reflective Practice: A Key to Learning from Experience - This video explores how reflective practice can enhance learning from experiences, offering insights into the benefits and application of reflective practice. Watch it here (YouTube).

Reflective Practice 101 - This introductory video explains the basics of reflective practice, including what to reflect on and why it is important. It is a great starting point for those new to the concept. Watch it here (YouTube).

Reflective Practice - This whiteboard animation provides a comprehensive overview of reflective practice, making complex concepts easier to understand through visual aids. Watch it here (YouTube).

These resources should provide valuable insights and examples to help understand and apply reflective practice in various contexts.

Conclusion

To recap:

- Reflection is serious and careful thought that helps the thinker to create meaning from an experience, and informs their decisions in the future for the benefit of themselves, and of others.

- Reflection can be undertaken in several ways, and one of these is to write it down.

- One method of organising this writing down process is to write to a reflective cycle.

- There are many reflective cycles: a useful one, and the one utilised in this module, is “Gibbs’ (1988) Reflective Cycle”.

- As with any learning by doing (also often called experiential education), the act of writing the reflection will help you write the reflection, and help you gain new thinking and writing skills.

Activity

Let's undertake a short reflective process. It might have been a field trip, or group or team work, or a tutorial or workshop you attended, or an activity you took part in, even an assessment you have done (it doesn’t matter if you got a more successful grade, or not). Complete each tab that steps you through the reflective process.

References

Bishop, G., & Blake, J. (2007). Reflective practice: A guide to reflective practice with workbook: For postgraduate and post-experience learners. University of Huddersfield. Retrieved from <//eprints.hud.ac.uk/19114/>.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. Touchstone.

Gibbs, G. (1988). Learning by doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. Further Education Unit, Oxford Brookes University.

Jasper, M. (2013). Beginning reflective practice. Cengage Learning.

Oxford Brookes University. (2018). Reflective writing: About Gibbs reflective cycle. Retrieved January 12, 2018, from https://www.brookes.ac.uk/students/upgrade/study-skills/reflective-writing-gibbs/.

Rodgers, C. (2002). Defining reflection: Another look at John Dewey and reflective thinking. Teachers College Record, 104(4), 842-866.

University of South Wales. (2013). Gibbs' model of the reflective cycle. Prifysgol. Retrieved from http://studyskills.southwales.ac.uk/media/files/documents/2013-08-21/Gibbs_Model_of_the_Reflective_Cycle.pdf.

Developed for the Practice and Portfolio Program for the Associate Degrees, University College, by Dr Christine Angel, 30 January 2018, updated August 2023 by Jenn Kemp Smith.