Analysis and Synthesis

Experiential Education

Objectives

What you will learn:

- What ‘analysis’ means.

- What ‘synthesis’ means.

- Why we analyse and synthesise, and how this can help us in the workplace.

- How to analyse and synthesise at university.

- How analysis and synthesis fits with a learning cycle.

- How to use a matrix to make analysis and synthesis easier.

What do these words mean?

‘Analysis’ and ‘synthesis’ are the noun forms of the verbs ‘to analyse’ and ‘to synthesise’. The plurals of the nouns are ‘analyses’ and ‘syntheses’.

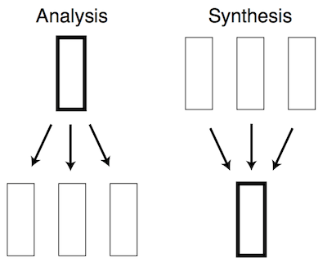

To analyse is to pull something apart: to give insights into the what, why, where, how, and who.

To synthesise is to draw on one or more sources and infer relationships among those sources in a new and meaningful way, and from which any reasonable person could make plans or decisions.

Analysis and synthesis are simply terms for what we do every day, often subconsciously. Think about driving, say from home to work. You don’t just jump in the car, drive, and arrive. You analyse (that is, you think about, and provide yourself with information about) the weather – your car’s capabilities – how far you need to travel and the time it will take – how you feel – the route you need to take – the likely traffic conditions – and so forth. You synthesise this information, and make meaningful decisions about the time you might need to leave, your route, whether you need to get fuel on the way, and so on.

Once on the road, you analyse the traffic – road conditions – traffic lights – pedestrians – road works: all the one hundred and one things of which a driver needs to be aware. You then act accordingly (synthesise): deciding which lane to take; when to slow down or speed up; whether you might need to stop in a hurry or swerve to avoid something. Most of the time this is done very quickly, sometimes in a split second. You analyse the situation, synthesise the results of your analysis, and act, or plan to act, accordingly.

Why do we analyse?

As can be seen above, we analyse to help us break down a possibly complex situation into more manageable parts, and to help us see and deal with the total picture a little more easily and clearly.

How can this help us in the workplace?

The skill of good analysis is one that we can take and apply anywhere: at home, in the community, at work. Here are some examples of how analysing can help us in the workplace:

- Applying for a job: for example, it can aid in completing a list of criteria. Sometimes these lists can appear overwhelming. Breaking them down into manageable parts can help us think logically and write appropriately.

- At the interview: considering, for example, what to wear, what to say, how to manage our time to ensure we are not late, and so on.

- In the work environment: understanding the role we are to fill, and the tasks we need to do to fill that role.

Why do we synthesise?

Once we have analysed possibly complex situations, we decide what we need to do, based on the results of the analysis. We also then need to put our decisions into action: planning, preparing, and applying.

How can this help us in the workplace?

For example, we can analyse, in the work environment, the role we need to fill and the tasks we need to do. However, we then need to stop analysing and start doing. Otherwise, we can fall into what has been called “analysis paralysis”, a situation where it is possible to do a lot of “work” but achieve very little.

See WritingforCollege.org (2013)

Application in the Study Environment

Analysis at university

According to Jewell (2013):

The word 'analysis' usually implies at least two elements: (a) A breakdown of something into parts or ideas, and (b) A discussion or description of those parts using a point of view or a method.

Let’s look at this quote bit by bit.

Breaking something down into its parts

Most assessment pieces at university require both analysis and synthesis. You might, for example, be asked to read some material and watch a YouTube video, then post, in MyLO, your responses to various questions. These questions will most likely start with ‘Why’, ‘how’, ‘who’, ‘what’, or ‘where’. To answer the questions, you will need to go to the reading material and the YouTube clip, and do a little research (search for the answers, that is). You will probably also have some knowledge from your own personal experience (tacit knowledge), which is also a valuable resource for research.

You will then sort through and think about what you have discovered from these various sources, decide which information is applicable to the question, and infer some relationships between the pieces of discovered information. Those relationships might be themes, patterns, recurrences, gaps, congruities, incongruities, and so forth. This will help you bring what might be a lot of material down into a manageable number of reportable findings (which is the beginning of synthesis).

Describing the parts using a point of view

When someone completes, for example, a PhD thesis, their work is sent to two or three examiners who are expert in the field. The examiners respond to the thesis, and decide whether it is of a sufficient standard to grant the applicant their PhD. A researcher asked several examiners what they look for when examining theses. Among the suggestions provided by the examiners are the following (Marshall 2011, pp. 1-13, emphasis added):

- Good analysis is not just finding out things (data*), sorting them into categories, and describing them.

- Good analysis creates an argument (that is, the writer puts forward a point of view based on their findings).

- Good analysis is reflective (see the module on Reflective Cycle).

- Good analysis can justify why the analysis is done in the first place.

The examiners had six related aspects they look for when examining a thesis (or essay, report, presentation etc.):

- A good read

- Authenticity

- Details stick in the reader’s mind

- Imaginative

- Well presented

- Well written.

* Data (singular is ‘datum’) = facts and statistics collected together for reference or analysis.

Academic synthesis

There are, according to the Michigan State University (2017, italics added), two types of synthesis: the ‘explanatory’ synthesis, and the ‘argument’ synthesis:

An explanatory synthesis helps people understand something. Something is analysed (pulled apart) to find its component parts (its what, why, where, how, and who). The component parts are then presented to the reader in a clear and orderly fashion. This type of synthesis does not go far beyond what is obvious to anyone who carefully reads the same sources. These notes are an example of an explanatory synthesis.

An argument synthesis goes a step further and deeper. It allows you to present your own point of view (known in academic circles as your ‘argument’), supported by relevant facts drawn from the sources, and presented logically. An argument synthesis makes a proposition that is debatable, about which any reasonable person could disagree – any two writers working with the same source material could conceive of and support other, perhaps opposing arguments.

Please see the 5 minute video below on analysis and synthesis (Ceraso 2015) as foundations of systems thinking.

Foundation of Systems Thinking

Synthesis Vs. Analysis | 4:05 mins

So What?

In most cases, your syntheses will need to be the second type: the ‘So what?’. Perhaps in your analysis you found a pattern of connections – but also a gap in the pattern. You might ask yourself (and give an opinion, or ‘argument’, on):

- What does the pattern mean? It might mean that there is a lesson to be learnt from it. It might be found to be meaningless – but this must be made explicit** in your synthesis.

- Does the pattern fit with other relevant patterns? Or is it different from other relevant patterns? How? Why? What do you think it means?

- What might the gap mean? It might mean that our analysis is wrong or needs adjustment – or it might mean that there is something that needs further investigation.

- The next question would then be: Why might it need further investigation? The answer might be that it may give us (you, those around you, the community in general) a better understanding of something/a better way to do things/a new product/a new way of looking at something.

For example, you might be asked to make explicit the drive from home to work. You would then need to explain, in words, each step of the journey, starting with the need to make it, the analysis you made of each of the aspects (weather, car condition etc.), the decisions you made and why, the actions you took as a result of those decisions, what actually happened on the drive, and whether you came to any new decisions for the future based on your experience.

Making explicit often simply involves writing down things we already know but don't always know we know.

Once you have answered the questions (both those posed by the teacher for the assignment, and those you will ask yourself as your research deepens) you will need to communicate your findings and your conclusions. That is, you explain clearly, fully, and succinctly, with no ambiguity, your findings and the relationships you have inferred from the various pieces of relevant information. Communication might be through a MyLO posting, or an essay, or blog, or presentation.

How does this fit with learning cycles?

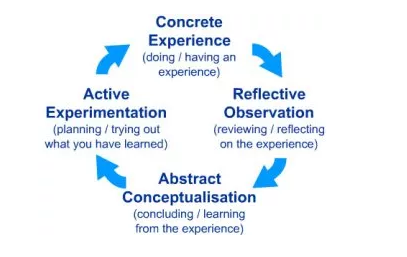

It might be easier to understand analysis and synthesis if we look at a learning cycle. A learning cycle is a concept of how adults learn from an experience. David Kolb (1984) proposed that learning is a process that can be modelled as a continuous cycle, as follows:

(Kolb 1984, p. 21)

(Kolb 1984, p. 21)

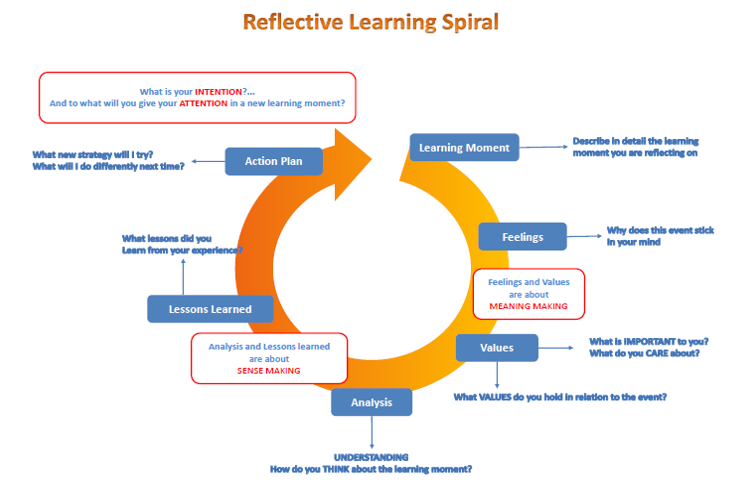

You will probably hear the name ‘Kolb’ a lot in relation to learning cycles. His model has been adapted by many theorists since 1984. The cycles have many different names: action learning cycle, reflective cycle, experiential learning cycle. Others suggest that the cycle is not a closed circle, but a continuous spiral. Here is an example that can help with reflection and reflective writing:

Prpic (2005)

Prpic (2005)

You will notice that the spiral deepens in colour as it moves around the cycle. This is to indicate deeper thinking as the cycle progresses. Here are the main sections:

- Learning moment: this is the experience (learning event, for example).

- Feelings and values: this is the very start of analysis. You start collecting a few facts about the experience.

- Analysis: this is when you consider the what, why, where, how, and who. That is, you start pulling apart the experience, to discover its component parts.

- Lessons learned: this is still part of the analysis. You are coming to some conclusions and making some decisions.

- Action plan: this is where synthesis kicks in. You can have all the information in the world at your fingertips, and have deep insights into yourself and the experience, but unless you take the next step to apply that knowledge, you can remain in “analysis paralysis”. Synthesis is when you apply your new understandings; that is, when you make plans to use what you have learned from the analysis, and even more, when you implement those plans

To summarise:

To analyse is to:

- Examine a situation or text to find its component parts in a way relevant to the particular requirements of the necessity for analysis.

- Come to logical and relevant decisions based on our findings.

To synthesise is to:

- Bring the component parts together again in a new and meaningful way.

- Utilise the results to make decisions and/or plans

- Then follow through with the decisions/plans

Activity

Linked to this module is a useful tool to help you break down your analysis and synthesis. You can use this matrix any time you need to, and for any analysis/synthesis situation.

For the sake of this exercise, we will stick with the theme of car travel. Think about the last time you drove somewhere. Consider all the hundreds of things you had to be aware of and plan to allow for before you actually started the engine. You will probably discover that there are too many items to even start writing them down.

You will find that this is usually the case when you are asked to analyse something, so you need to select a relevant aspect, and concentrate on that (mentioning in your write-up that this is what you have done). In this case, let’s concentrate on thinking about the driving conditions.

I have put a few into the matrix to start you off.

As you will see, analysis and synthesis of the over-all driving conditions requires analysis and synthesis of all the various aspects. More likely than not, each aspect can combine to change the outcome of the over-all synthesis. For example, driving on a rainy day, on wet roads, at night, would mean you would make different plans than if you were going to drive on dry roads during sunny daytime.

Over to you to put in a few more, into any of the columns and rows. If you wish, you can then upload it as an artefact into your Unit or Professional Portfolio.

ANALYSIS AND SYNTHESIS MATRIX EXAMPLE - DRIVING CONDITIONS

| TO BE CONSIDERED (for example) | DETAILS (examples) | DATA/EVIDENCE | SOURCE/S OF DATA (reference) | ANALYSIS (Reflection and Analysis) | SYNTHESIS (Decisions, Planning and Putting into Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weather | Rain Wind Snow Sunny Clear | Example Rain | Own Observation, Bureau of Meteorlogy, Radio, Internet, Other Media, Other People |

|

|

| State of the roads | Wet, Icy, Sealed, Gravel, Muddy | Example Wet, Muddy | Own observation Radio Internet Other people | ||

| Traffic | Thin, Thick, Fast, Slow | Example thick,fast | Own observation, Radio Internet, Other people | ||

| Time of day | Peak hour | School time | Night | ||

| Example night | Or peak hour at night | Or school time, and peak hour, at night | Own pre-knowledge, Own Observation | ||

| Other | Accidents, Road races |

References

Ceraso, G 2015, ‘Analysis v. synthesis’, YouTube video, viewed 11 July 2017, <https://youtu.be/JdP1S0qj5vg>.

Kolb, DA 1984, Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs.

Marshall, H 2011, ‘‘Good’ qualitative analysis – examiners’ views’, Proceedings of the 2011 TASA Conference: Local Lives Global Networks, Newcastle, Australia, 28 November - 1 December, 2011, pp. 1-13.

Michigan State University 2017, Introduction to syntheses, viewed 13 June 2017, <https://msu.edu/~jdowell/135/Synthesis.html#anchor48017>.

Prpic, JK 2005, Reflective learning spiral, viewed 13 June 2017, <http://cmapspublic.ihmc.us/rid=1PC8NRGW0-2BL1DL-2GNL/ReflectiveLearningSpiral-JKayaPRPIC.cmap>.

WritingforCollege.org 2013 ‘Analysis’, viewed 22 June 2017, <http://www.tc.umn.edu/~jewel001/CollegeWriting/WRITEREAD/Analysis/default.htm>.

Source of Images

Analysis and synthesis: 13 June 2017 from: <http://www.solvingforpattern.org/2013/04/24/a-science-of-analysis-synthesis/ >.

Module Creator/Author: Dr Christine Angel, 16 July 2017