Respecting the Individual and Their Context

ZAC101 | 2.1 | Self-awareness - who are you?

Introduction

As a society, we generally expect those working in health and community services to be ‘professional’, but this is a term that is difficult to define. What does it actually mean to be professional? How can one develop their personal sense of self, and how might this interact with their professional identify and performance?

We will begin to consider these questions by exploring self-awareness and the importance of understanding your own values, beliefs and motivations. This will, in turn, assist you to better understand the unique experiences and ‘world views’ of others, and to develop and nurture the personal and professional relationships that are essential for quality practice in this sector.

As highlighted in Week 1, our suitability for work in the health and community services sector includes consideration of our so called 'soft' skills, in addition to our technical knowledge and proficiency. Soft skills – those learned through social and environmental interactions – are essentially people skills, which are often the focus of the values-based staff recruitment approaches adopted by many health and community service organisations.

Many of these 'soft skills' are underpinned by our developing awareness of self and others (the focus of ZAC101), which is broadly exemplified by the concept of Emotional Intelligence (EI)'. Emotional intelligence is sometimes referred to as emotional quotient (EQ), which can be considered in a similar way to the more common, intelligence quotient (IQ). So people can be emotionally 'smart'.

There is now a growing recognition that in a profession that promotes 'caring', 'relationships' and 'respect' as core principles, workers must be able to combine their technical knowledge and expertise and their emotional capabilities as a means of strengthening relationships, improving the quality of decision-making, and better managing or coping with the emotionally-laden situations and complex communication challenges encountered in their practice (Arnott et al. 2019).

What is Emotional Intelligence?

What does it mean to be 'intelligent'? In considering this question, we may often think of the common (but narrow) definition of intelligence as being knowledgeable or clever, but the idea of 'emotional intelligence' has more-recently emerged as a key component of overall intelligence and vital to the development of well-rounded or 'balanced' individuals (Goleman et al. 2013; Mayer et al. 2008). The importance of emotions in learning, decision-making and relationships has long been evident. For example, the ancient philosopher, Plato, argued that 'all learning has an emotional base'; and the 19th Century scientist, Charles Darwin, emphasised the importance of emotional expression for survival and adaptation in his theory of evolution. The idea of multiple 'intelligences' began to take hold in the 1920s when the concept of 'social intelligence' emerged in reference to the skills needed to understand one’s own and others’ emotions and to act wisely in human relations (Arghode 2013).

Although there is no single or common definition of emotional intelligence, it is generally accepted that it involves the ability to perceive and understand one’s own and others’ emotions and to use this information to guide thinking and behaviour (Goleman 1998; Goleman et al. 2013; Mayer et al. 2008). The video below provides an overview of emotional intelligence and its importance in personal and professional domains.

What is Emotional Intelligence? | 5:28 mins

According to Mayer et al. (2004), emotional intelligence involves four interrelated components or 'branches': perceiving emotions in ourselves and others; using this emotional input to facilitate thinking (cognition); understanding the messages or meanings conveyed by these emotions; and managing emotions by promoting actions and behaviours that benefit ourselves and our relationships (personal and emotional growth). The short animation below outlines these four branches to show how EI forms an integral part of our thinking and decision-making.

Emotional Intelligence | 2.51 mins

Activity: Emotional Intelligence Quiz

Understanding the emotions of others requires skill at interpreting a variety of verbal and non-verbal information. In many professional situations, verbal information may not be clear or readily available and we therefore need to rely on our ability to read cues such as facial expressions, eye-contact and body-language.

Take this short quiz from the Greater Good Science Centre at the University of California, Berkeley, which assesses your emotional intelligence based on the interpretation of facial-expressions as a universal language of emotion.

Test your emotional intelligence here

How did you go? Were you surprised by any of the answers? Did you find any emotions confusing or difficlut to recognise?

The five components or 'pillars' of emotional intelligence

Building on the work of Mayer and colleagues, Daniel Goleman, a psychologist and best-selling author in the area of emotional intelligence, introduced the notion of EI consisting of five different components or pillars, as outlined below (Arnott et al. 2019; Cherry 2018):

1. Self-Awareness

The ability to recognise and understand your emotions, moods and actions and how these affect others. It includes having awareness of our personal abilities, strengths and limitations, and being open to different experiences and new ideas. Self-awareness also requires us to recognise that how we feel and what we do (or say) are related, and the importance of noticing and giving mindful attention to the ways we 'react' to different situations or to the emotions, moods and actions of others.

2. Self-Regulation

The ability to regulate, control or redirect disruptive impulses, moods or reactions and to think before acting (suspend judgement). It includes being flexible, and the ability to cope with change, to diffuse difficult or tense situations, and to manage conflicts effectively. It also refers to being aware of how one's actions affect others and taking ownership of these actions.

3. Motivation

An intrinsic motivation and passion to act (e.g. work) for reasons that go beyond money, status or recognition. It involves being action oriented, with a desire to set and pursue goals with energy and persistence, to take initiative and to search for ways to improve.

4. Empathy

Being aware of and sensitive to the feelings of others, or to perceive and share in another person's reality. Empathy enables us to sense power dynamics that play a part in relationships (especially our professional or workplace relationships), and to perceive and understand the situations in which these power dynamics may come into force and how they affect the feelings and behaviours of all concerned.

5. Social Skills

The ability to interact effectively with others. It requires sensitivity to one's own and others' emotions and an ability to find common ground, build rapport, and to lead, motivate and resolve disagreements with others.

Several of these components are focussed on our interactions and relationships with others, which we will consider further in coming weeks. For this week, however, we plan to focus our lens 'inwards' (on ourselves), through some examination of the first two pillars: Self-Awareness and Self-Regulation.

Test your knowledge on the five 'pillars' of emotional intelligence.

Self-awareness

The core of emotional intelligence is self-awareness.

You have probably been told or heard the saying: "be/stay true to yourself". This may be great advice for both your personal and professional lives, but how can you stay true to yourself (or even know that you want to) if you don't really know who you are? Thus, the age-old adage of 'know thyself' seems to be a fitting starting point for any journey of personal or professional discovery (learning, growth and development).

Self-awareness (sometimes referred to as introspection or self-knowledge) is about who you are and what makes you tick - the things that influence, motivate, inspire and challenge you. It is about understanding your own values and beliefs, your needs and preferences, your strengths and limitations, and your attitudes, habits and biases. It involves recognising how your thoughts and emotions influence the way you act, behave and/or respond to different situations and experiences, and understanding the internal resources you have for managing or regulating these things.

In the context of emotional intelligence, self-awareness is comprised of three key competencies: emotional self-awareness, where one is able to perceive and understand their emotions and how they impact on work performance and relationships; accurate self-assessment, where one is able to realistically evaluate their abilities, strengths and limitations; and self-confidence, where one has/develops a positive and strong sense of self-worth.

The key starting point for each of these areas is the ability to be critically self-reflective. We will be prompting and encouraging critical reflection throughout this course, but you might like to extend your understanding at this stage by reading the Practice & Portfolio resource on the Reflective Cycle (models and frameworks for reflective practice and reflective writing).

Why is self-awareness important?

Research suggests that when you are self-aware, you are far more likely to pursue the right opportunities, make good decisions, put your strengths to work, and keep your emotions, impulsive reactions or negative self-talk from holding you back (Bradberry & Greaves 2009; Goleman et al. 2013). Bradberry and Greaves (2009) profiled the characteristics of people from different walks of life. They found that highly self-aware people tended to be open and authentic, honest about their feelings and ‘cool, calm and collected’ in times of stress or crisis; whereas those low in self-awareness were more likely to project stress and urgency, be defensive, aggressive or demanding, and fail to notice how they affect others. The more you pay attention to your values, emotions and how you act, the better you'll understand why you do or say the things you do. The more you know about your habits, biases, reactions and behaviours, the easier it will be to regulate or improve these things.

Self-awareness is considered a key requisite for self-regulation, self-management and self-improvement. Being mindful of your weaknesses allows you to set goals and implement strategies for better managing these limitations. Paying attention to your strengths can also contribute to self-improvement by developing ways in which you can more readily harness and deploy these positive resources in times of stress, emotional-turmoil or conflict.

As we will discuss in future weeks, self-awareness is also key to understanding others. Greater self-awareness creates a clearer lens through which to see other people as distinct individuals, and to better understand their particular perspectives, emotions and behaviours, without judgement. Self-awareness doesn’t automatically make you more aware of others, but it can promote more mindful attention to those around you. It also helps you to identify your likely feelings and reactions to various situations, to recognise the triggers for these emotional responses, and to use these insights to inform any improvements required to be more responsive to the unique, subjective world of those you are interacting with. Likewise, exploring the emotions, needs and views of others may help to recognise, affirm, accept or change certain aspects of your own ‘self’, thereby making you more present, authentic and compassionate in your interpersonal relationships with others.

There is no denying that self-awareness is critical for your success as a health and community services professional. As human service workers, you will often form and maintain relationships within emotionally-charged environments, and provide complex care for people who are emotionally vulnerable. Every situation or experience will evoke an emotional reaction, derived from your own value base or belief system - your personal 'world view'. The dilemma, however, is that in many interactions and experiences, these emotions often manifest subconsciously (without us knowing) or we simply operate on 'auto-pilot', making self-management and self-improvement much more difficult.

For example, there are various cognitive biases (set ways our brain thinks) that can cloud our ability to understand ourselves, or trick us into interpreting information in a way that confirms our preconceptions or memories of something. This idea is expanded upon by Daniel Kahneman, a Nobel Prize winner for his contribution to behavioural science, who talks about the difference between the 'experiencing self' and the 'remembering self', and how it can affect our decision-making.

The riddle of experience vs memory, Daniel Kahneman | 20.36 mins

So, while the 'what' and 'why' of self-awareness can be easily defined, the actual ability to be self-aware and to bring this awareness to your interpersonal interactions requires dedicated focus and practise (Arnott et al. 2019).

How can you enhance your self-awareness?

There are many ways to cultivate greater self-awareness, for example:

- Meditation/Mindfulness training (you might like to check out Smiling Mind, an Australian not-for-profit organisation that works to make mindfulness meditation accessible to all. Their website provides access to a range of programs and resources that aim to build happier, healthier and more compassionate people. They also provide a ‘mindfulness meditation app’ that can be downloaded for free, allowing you to practice mindfulness anytime, anywhere and every day!).

- Goal setting - working out where you want to go in life and how you will get there.

- Keeping a journal (setting up a learning & practice journal in your PebblePad Portfolio is a great place to start).

- Regularly reflecting on and evaluating your ideas, behaviours and performance.

- Learning to give and receive honest and constructive feedback.

- Asking trusted colleagues, friends or family members to provide honest appraisals of how they perceive you and your particular strengths and weaknesses.

- Taking psychometric tests.

Values, beliefs, attitudes and behaviour

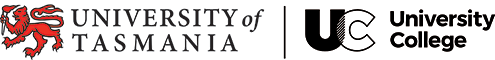

As human beings, we all have our own values, beliefs and attitudes that contribute to our sense of who we are and how we view the world, and influence the way we act or behave.

Beliefs are the convictions or ideas that we believe to be true. Beliefs underpin our actions and behaviours, and provide explanations of how we understand ourselves, our world, and the things that happen to us (our experiences). Beliefs may be based upon certainties (e.g. mathematical principles; actual experiences), probabilities, or matters of culture or faith. They may arise from different sources, including:

- A person's own experiences or experiments;

- The acceptance of cultural, familial and/or societal norms (e.g. religion);

- What other people say (e.g. education, mentoring, socialisation)

Each person evaluates and seeks sound reasons or evidence for their beliefs in their own ways. Once a person accepts a belief as 'truth', it forms part of their belief system that they are willing to defend (although beliefs may change or cease based on the person's ongoing experiences and evaluation). Sometimes beliefs may be considered or described as a value, based on the premise that certain beliefs may matter more, or be more important or valuable to a person (see the image above).

Values are those things that really matter to us – the principles, standards or qualities that an individual or group of people hold in high regard. Because they really matter, values greatly influence how we think, feel and behave, and the choices or decisions we make.

Attitudes are the mental dispositions and behavioural tendencies that a person may have and direct towards other people, groups, ideas, or circumstances. People primarily form their attitudes from underlying beliefs and values. Attitudes can sometimes reflect our values (things that really matter to us), but if not so important, they may be more like a personal opinion on something. Sometimes our own attitudes can make us blind to other people's beliefs, values and needs, lead us to behave or respond in a certain way toward that person or group (stereotyping), or cloud our judgement in meeting other people's needs (basing decisions on what we think someone should do, rather than their own values, beliefs and needs).

Our values, beliefs and attitudes are influenced by a range of things/sources, including:

- Culture and society

- Family

- Peers and social networks

- The workplace (including organisational culture; work ethics; and discipline perspectives

- Educational institutions and experiences

- Significant life events (e.g. births, deaths, relationships, trauma, accidents, health issues, significant financial changes, etc)

- Religion

- Media

- Major historical events

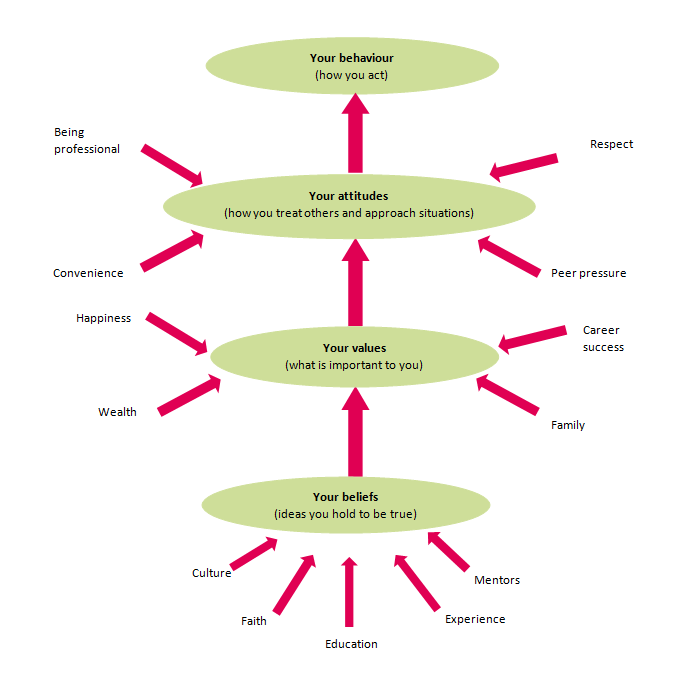

These ideas are captured in the following image.

Did you realise that every single one of your behaviours arises from a complex mix of everything that operates 'below the surface' of the iceberg?

It is important to realise that most elements within the iceberg and their influence on your thinking and behaviour are constantly changing, and you can learn to exert conscious control over the outcome.

Being aware of (and critically evaluating) your values, beliefs and attitudes is particularly important for health and community service professionals. We need to establish and maintain meaningful and empowering relationships with clients and colleagues who may sometimes have very different values, beliefs, attitudes or needs to our own.

These will form the core focus of our Week 2 workshop and first assessment task, but to get you into this mindset, you may like to re-visit the 'What Really Matters' activity from week 1, or work through the Practice & Academic Toolbox Module on Values and Virtues.

Strengths-based perspective

Strengths-based practice is a key underpinning for this unit (and the entire course). This recognises that many of the systems, models, policies and institutions that exist in the health and community service sector emphasise a 'deficit' perspective, whereby issues and needs are viewed as 'problems' (often attributed to the individual) that need to be treated, fixed or cured. Rather than attuning to this 'deficit' mentality in our own practice, we will seek to explore the principles and ideas behind strengths-based practice, which is a respectful and empowering way of considering people's capabilities in terms of what they 'can' do.

We want you to begin this journey by considering your own character strengths and how these can be effectively harnessed and deployed to enhance and improve your professional practice. For assessment task 1 (see page 2.3), you will be required to complete the VIA (values in action) Character Strengths Survey, which considers your core characteristics with a particular focus on "your best qualities" rather than negative or neutral traits.

References

Arghode, V. (2013). Emotional and social intelligence competence: Implications for instruction. International Journal of Pedagogies and Learning, 8(2), 66–77.

Arnott, N., Paliadelis, P., Cruickshank, M., & Williams, D. (2019). Understanding self and others. In N. Arnott, P. Paliadelis, & M. Cruickshank (Eds.), The Road to Nursing (pp. 152-167). Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

Bradberry, T. & Greaves, J. (2009). Emotional intelligence 2.0. San Diego, CA: TalentSmart.

Cherry, K. (2018). 5 Components of emotional intelligence. Very Well Mind. Retrieved from https://www.verywellmind.com/components-of-emotional-intelligence-2795438

Craig, H. (2019). The theories of Emotional Intelligence explained. Positive Psychology program. Retrieved from: https://positivepsychologyprogram.com/emotional-intelligence-theories/

Goleman, D. (1998). Working with emotional intelligence. New York: Bantam Books.

Goleman, D., Boyatzis, R., & McKee, A. (2013). Primal leadership: Unleashing the power of emotional intelligence. Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Review Press.

Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., & Caruso, D.R. (2004). Emotional intelligence: Theory, findings and implications. Psychological Inquiry, 15, 197 – 215

Mayer, J.D., Salovey, P., & Caruso, D.R. (2008). Emotional intelligence: New ability or eclectic traits?. American Psychologist, 63(6), 503-517.

Big five personality traits -

https://www.123test.com/big-five-personality-theory/

Change Management Coach -

https://www.change-management-coach.com/self-awareness.html

Global Leadership Foundation -

https://globalleadershipfoundation.com/deepening-understanding/emotional-intelligence/

Acknowledgements - content contributor Matty Harrison