The Dangers of Leadership

Experiential Education

Objectives

On completing this module, you will have a better understanding of some of the dangers that can face leaders as they fulfil their leadership role. Some of these dangers can come from outside, and some from the leaders themselves.

This module isn’t about good leadership or bad leadership – it’s about the dangers leaders potentially will encounter as leaders.

Introduction

We often think of ‘leaders’ as being other people – the big names, the people who coordinate our teams, even our bosses. However, we can all take on a leadership role, whether it is within classrooms, board rooms, family circles, or the community. This might be, for example, as group discussion facilitators, CEOs of our own companies, sports team leaders, or dealing with family matters. Taking on leadership responsibility can come with its own risks. Being aware of the risks can help us avoid some of the pitfalls, or manage them as or before they arise.

Of course, leaders do not always face all or even any of these dangers all the time – and the dangers might be to a lesser or larger degree from time to time. However, at some stage in the leading process, there are circumstances where the leader needs to be on the alert, so they do not fall into the traps, or allow others to do so.

There is a fable (a story with a moral or life lesson), attributed to the ancient Greek fabulist Aesop, about a fox and a boar. The fox laughed at the boar for sharpening his tusks even though there was no sign of danger. The boar responded that when danger did arrive, he wouldn’t have time to sharpen his weapons, so he stayed prepared. It is the same with leaders.

Before going any further in this module, we suggest you refresh the understanding of leaders and leadership provided in the Adaptive Leadership and Leading Change modules. They explore the concepts of ‘me’ (understanding ourselves) and ‘we’ (applying that understanding to ourselves and others, especially as leaders). They include knowing our own talent and values, and reflecting and reframing (making meaning from sometimes adverse situations). The modules also provide a few strategies for being an adaptive leader and coping with change in a rapidly-changing world.

The Dangers: An Overview

Sometimes we step up into a leadership role unexpectedly, sometimes the role is forced upon us, and sometimes we choose to be the leader. Leadership can bring great benefits, to the leader, to those whom they lead, and to the group or organisation of which they are a part. Being aware of the dangers is just another facet of the role.

A lot has been written about the pitfalls that leadership can bring. This module does not cover them all, but is an overview of some of the main ones as discussed by well-known and experienced authorities in the field of leadership.

To lead is to live dangerously...

Ronald Heifetz and Marty Linsky (2017, p. 2), who have researched and taught leadership at Harvard University for many years, suggest that:

to lead is to live dangerously because when leadership counts, when you lead people through difficult change, you challenge what they hold dear—their daily habits, tools, loyalties, and ways of thinking.

They list four dangers to which leaders can be open from others, including from within their own organisation:

- Being marginalised

- Being diverted

- Being attacked

- Being seduced

Other authors discuss different dangers. Here are a few:

Anders Skogstad, Ståle Einarsen, Torbjørn Torsheim, Merethe Aasland and Hilde Hetland (2007), from the University of Bergen in Norway, talk about the challenges of ‘laissez-faire’ or ‘hands off’ leadership.

Conversely, Blake E. Ashforth (1997), an organisation researcher and writer, suggests that there is a danger of leaders falling into ‘petty tyranny’ behaviour, where they ‘lord it over’ everyone.

This ties in with work by Wallace A. Burns, Jr (2017), who recently undertook a review of what he called ‘harmful’ leadership styles, Dan Rockwell (2014), a leadership blogger, and Manfred F.R. Kets de Vries (2015), whose work focuses on leadership and organisational change. These authors could be said to talk about uncaring leadership.

Being human beings, leaders are also subject to making mistakes. Being aware of the dangers can help us all navigate the pitfalls to which leadership can be prone.

If you want to succeed, make life better for others.

The Four Dangers

First, let’s look at some dangers to which leaders are open from others that Heifetz and Linsky (2017, pp. 31-48) warn about.

1. The danger of being marginalised

In his YouTube video, Marty Linsky: Risky leadership, Linsky (2010) explains:

People who exercise leadership push against the prevailing wind. They deliver messages that people don’t want to hear. They try to get people to face up to difficult issues that they prefer not to face up to. And so people who try to exercise leadership meet resistance and that resistance makes people vulnerable and that puts you [as leader] at risk. You take chances of losing your position and getting marginalised and pushed aside.

Here is the video if you would like to watch it all (1min 15sec):

Marty Linsky: Risky leadership | 1:15

Marginalisation (or treating a person as insignificant, not worth listening to) can occur when leaders:

- say something so often that people tune out. This can happen particularly when we are passionate about something. There is nothing wrong with having an attention focus but we must be careful not to let it over-rule leadership to the point where nobody listens any more. We must choose the moment and the audience.

- stray outside what others perceive as their area of expertise – especially if they stray into what others believe are their expertise areas.

- do not fit the stereotype of what others think should be leaders. This can include issues of gender, sexuality, ethnic origins, age, beliefs and so on. This situation can also lead to ‘tokenism’, or being given a role based on one of those characteristics.

2. The danger of being diverted

Leaders run the risk of being kept diverted from their main task of leading. Sometimes we as leaders ‘collude’ by not looking behind the offers that are made to us. These offers can be authentic, sincere and well-earned. However, sometimes they are not, and leaders can be open to being ‘kept busy’.

Diversion can take the form of:

- Promotions, or seemingly enjoyable or glamorous new responsibilities.

- Numerous board or committee appointments.

- Becoming lost in others’ demands and agendas.

- Being given so much interesting work that the list of tasks becomes insurmountable and nothing actually gets done.

3. The danger of being attacked

Leaders are at risk of being attacked, especially now with the Internet and social media. Rather than focus on the leader’s message, people will try to discredit them. Consider how often public figures (such as politicians, film and television personalities, and sports people) are maligned, sometimes quite appallingly.

Be aware that this can happen to us as leaders. The attacks might take the form of:

- An emotional attack: turning a conversation from the topic of discussion to the leader’s character or style. When the message is not what attackers want to hear, they can suggest the leader is ‘too abrasive or too gentle, too aggressive or too quiet, too conflictive or too conciliatory, too cold or too warm’ (Heifetz & Linsky 2017, p. 41).

- A physical attack: violence, from minor to the ultimate, can divert attention from an unwanted issue.

- Misrepresentation, such as twisting a leader’s words, or taking the words out of context. Or even going back to a youthful indiscretion that does not reflect the leader as they are today.

Such attacks can hurt, and it is difficult to resist responding. However, one way attacks can be handled is by holding on to our integrity and values: by remaining as ethical and honourable as possible.

4. The danger of seduction

This doesn’t refer to the danger of improper advances. It is when leaders succumb to a temptation that might make them lose their sense of purpose. This can take the form of:

- Desire for approval from their own supporters. While such support can give a leader courage and confidence in what they are trying to do, it can also lead to a lowering of capacity to think and act purposefully and objectively.

- Trying to stay loyal to those around them, but losing sight of the big picture.

- Others becoming too dependent on them, and not learning to make the hard decisions.

These four dangers, marginalisation, diversion, attack, and seduction, are some of the challenges that we risk incurring as leaders. The next few dangers relate more to the way we behave as leaders.

The Dangers From Leader Behaviour

Every leader has their own way of leading, and their own way of behaving while leading. There are many leader types and leadership styles, and they have been categorised in many different ways.

For example, in 1939 Kurt Lewin, an early psychologist, with a group of researchers came to the conclusion that there were three main types of leadership: autocratic, democratic and laissez-faire (Cole 2013, p. 255).

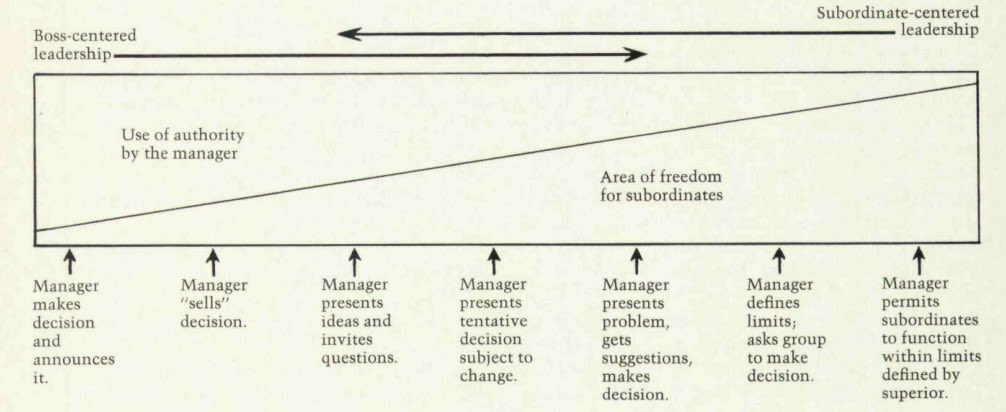

A few years later, in 1958, Robert Tannenbaum and Warren Schmidt suggested that rather than being in distinct categories, there is a continuum of leadership styles (behaviour) ranging from those who exercise a high degree of control over those whom they lead to those who do not. Here is a copy of their original continuum (1973 reprint, p. 164):

Note: this early continuum refers to bosses, managers, and subordinates; most of today’s models refer to leaders and employees, and the continuum might refer to a flow from independent leadership to interdependent leadership.

Independent leadership refers to a more traditional style where the leader makes all or most of the decisions, whereas interdependent leadership is usually where the leader adopts an approach of mutual decisions and achievement (Morrison 2007, pp. 83-85).

While each style of leadership has its place depending on the circumstances, each can also bring its own dangers.

Here, we’ll look at two of the leadership dangers that fall into categories at the extremes of the continuum: petty tyranny, and laissez-faire leadership.

The danger of ‘petty tyranny’, or ‘the tendency to lord one’s power over others’

A danger for leaders is to become too authoritarian and micromanaging – to become a ‘petty tyrant’. Ashforth (1997, p. 126) suggests that a petty tyrant ‘lords their power over others’. Leaders who practise petty tyranny, according to Ashforth (1997), tend to use their authority to demand their own way and not consider the welfare or input of others.

This type of behaviour can, according to Ashforth (1997, p. 128), cause frustration and low performance among those whom they lead. And, of course, it can cause lack of respect and decreased desire to follow that leader.

Petty tyranny, according to Shazia Akhtar and Kiran Shaukat (2016, p. 282), plays a significant role in ‘work alienation’. Work alienation, put simply, is when someone feels that what they do is meaningless – they feel alienated from what they do. However, ‘people are looking for more meaning and purpose in their work lives. They want . . . to be valued’ (Hill 2010).

According to Akhtar and Shaukat (2016, p. 276), the relationship between a leader and those whom they lead is ‘very important for . . . organizational success’ and can make the difference between good and low productivity.

The dangers of laissez-faire or hands-off leadership

This danger is at the other extreme of the leadership continuum – laissez-faire leadership. Laissez-faire leadership is when the leader delegates all responsibility to those whom they lead, so that group members solve problems on their own, but leaders still take responsibility for the group’s decisions and actions.

While this style of leadership can work effectively with the right leader and the right group of people, the danger is when the leader takes the ‘hands-off’ approach to the extreme. Even with the best intentions of empowering the group, taken too far there is the danger that the group feels disempowered. This is especially so when the roles and responsibilities of the group and its individuals are not clearly defined.

This can be ‘counterproductive’, leading to a workplace that is characterised by role ambiguity and interpersonal conflicts (Skogstad et al. 2007, p. 89). While role ambiguity can be alleviated by the leader providing clear messages about responsibilities, goals and priorities, interpersonal conflict, if not avoided or mitigated, can lead to bullying.

. . . forceful bosses who discourage initiative can cause a lot of suffering among their employees, but so can do nothing bosses who deliberately avoid the task of directing their staff.

I remember one of my bosses, whom I consider to be a great leader, saying to me: ‘I like to give my staff a lot of leeway, but I keep an eye on them, and, if things go pear-shaped, I take ultimate responsibility, because I am their leader’.

The dangers of ‘uncaring’ leadership

Morrison (2007, p. 88) reminds us that ‘they don’t care what you know until they know that you care’. He suggests that leadership is not something that we do, or that we do to others – it is a relationship. In other words, the leader is not alone, but working for and with others.

The caring leader therefore needs to be aware of the dangers of not considering the people whom they lead. This can manifest in many ways. Some of them are mentioned above under ‘petty tyranny’.

Burns, in his 2017 review of research on what he calls ‘harmful’ leadership styles, considers that there are several behaviours common to most of them. While the list of behaviours includes such items as harassment, deception and taking credit for others’ work, the behaviours towards their followers that were common to the harmful styles Burns studied are:

- Demeaning, marginalising or degrading

- Ridiculing or mocking

- Social exclusion

- Blaming others for their own mistakes.

Rockwell (2014) and Kets de Vries (2015) also warn against the dangers of being a leader who

- Does not know or understand themselves, let alone those whom they lead

- Indulges in hubris – that is, they become arrogant and out of touch with reality

- Does not control their emotions – ‘outbursts erode respect' (Rockwell 2014)

- Is not open to adaptation and change

- Is not open to criticism or dissent

- Ignores office politics

- Acts selfishly – ‘advantaging’ themselves when opportunity arises, rather than advantaging others

(adapted from Rockwell 2014 and Kets de Vries 2015)

Recap

We can all be leaders at some time, and leadership can bring great benefits, to the leader and to others. We each have a style of leading, that is, a way we tend to behave as leaders. Leadership can be risky, however, and sometimes we can fall into one of the pitfalls that come with leadership. Being aware of the dangers can help us to avoid them.

The dangers can come from outside, or from within ourselves.

The dangers that can come from outside include:

- Being marginalised by people tuning out from our message, or feeling like we are stepping into what they consider to be their area of expertise, or when we don’t fit a stereotype of what people think of as ‘leaders’.

- Being diverted from our main task by being given attractive roles that might have no real substance and keep us away from what we really should be doing.

- Being attacked, in print, online, or in person. Leaders often become open to public scrutiny, and people are not always kind, especially if they do not hear what they want to hear, or the leader does not do what people want them to do.

- Being seduced by the need to feel liked, or to be loyal to those around them, which can lead to difficulty making the hard decisions.

The dangers from our own behaviour, which each of us as leaders need to remind ourselves about from time to time, include:

- Being a petty tyrant, or using our power to do things our way, without considering the value of others’ input.

- Being too laissez-faire or ‘hands-off’ to the point of disempowering our followers, rather than empowering them.

- Being a leader who doesn’t care about their followers as people. This can include not understanding themselves therefore being unable to understand or assist others, blaming others for their own mistakes, being arrogant or ill-tempered, or acting selfishly.

All the above dangers could be said to be extremes, and we as leaders might not experience any or all of them during our leadership. However, they do occur, even if we are fulfilling our leadership role to the finest of our ability. It is best, like the boar, to be prepared: to enjoy the benefits, and avoid the dangers.

Activity

Think of three leaders on the world stage, then answer the following questions:

- What dangers are those world leaders subject to?

- Why do you think they are subject to them?

- How could they avoid the dangers?

Next, think of three leaders in your community. They might be in politics, in your church, in your social group, or family, or classroom. Ask the same questions about them.

Now, think of an instance when you took on a leadership role yourself. This might be as simple as being the main speaker when making an assignment presentation. It might be you in a community role, or in your sporting team. Choose one, then ask yourself the same questions.

Also: did you face and overcome any of the dangers in that leadership role? What was the danger?

Make a short note about the incident, how you overcame the danger, and how you might approach a similar situation in the future now that you have learnt from the experience, and know a little more about the dangers. Yes, you're right, this sounds like the Gibbs’ (1988) reflective cycle – if you’d like to follow that cycle to answer your questions, here is the link to the ‘Reflective Cycle’ module:

If you would like to answer the questions directly into PebblePad, here is a link to the template. Save your completed template into your list of Assets, and, if you wish, add it to your Practice Manual (we suggest your Professional Portfolio under ‘Leadership’).

References

Akhtar, S & Shaukat, K 2016, ‘Impact of petty tyranny on alienation from work: role of self-esteem and power-distance’, Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 275-85.

Ashforth, BE 1997, ‘Petty tyranny in organizations: a preliminary examination of antecedents and consequences’, Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 126-40.

Burns, WA Jr 2017, ‘A descriptive literature review of harmful leadership styles: definitions, commonalities, measurements, negative impacts, and ways to improve these harmful leadership styles’, Creighton Journal of Interdisciplinary Leadership, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 33-52.

Cole, K 2013, Management theory and practice, 5th edn, Pearson, Frenchs Forest.

Heifetz, RA & Linsky, M 2017, Leadership on the line: staying alive through the dangers of change, Harvard, Boston, Mass.

Hill, LA 2010, ‘Leading from behind’, blog, 5 May, Harvard Business Review, viewed 23 October 2019, <https://hbr.org/2010/05/leading-from-behind>.

Kets de Vries, MFR 2015, ‘Leadership lessons from the Brothers Grimm’, blog, Leadership & Organisations, viewed 19 September 2019, <https://knowledge.insead.edu/blog/insead-blog/leadership-lessons-from-the-brothers-grimm-4016>.

Linsky, M 2010, Mart Linsky: risky leadership, YouTube video, viewed 20 September, 2019, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NcRk8RBFxeY>.

Morrison, M 2007, The other side of the card: where your authentic leadership story begins, McGraw Hill, New York.

Rockwell, D 2014, ‘”Advantage” solves the 12 dangers of leadership’, blog, Leadership Freak, viewed 17 September 2019, <https://leadershipfreak.blog/2014/11/08/how-advantage-solves-the-12-dangers-of-leadership/>.

Sidle, SD 2007, ‘The danger of do nothing leaders’, Academy of Management Perspectives, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 75-77, DOI: 10.5465/AMP.2007.25356514.

Skogstad, A, Einarsen, S, Torsheim, T, Aasland, MS & Hetland, H 2007, ‘The destructiveness of laissez-faire leadership behaviour, Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, vol, 12, no. 1, pp. 80-92.

Tannenbaum, R & Schmidt, WH, 1958, ‘How to choose a leadership pattern’, Harvard Business Review, March-April. Republished Harvard Business Review May-June 1973, pp. 162-80, viewed 26 September 2019, <http://eds.b.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.utas.edu.au/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=4&sid=e45d50b3-4415-4c0a-b30b-9e499a4aa965%40pdc-v-sessmgr04>.